By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

“Because consumer debt servicing statements are typically furnished to credit bureaus only once during every statement period, our snapshot of consumer credit reports as of March 31, 2020 is, in effect, largely a pre‑COVID‑19 view of the consumer balance sheet,” the New York Fed said today when it released its Report on Household Debt and Credit for Q1. So the credit-upheaval caused by the biggest and most sudden unemployment crisis in our lifetime is not yet included in the New York Fed’s delinquency data. But even in the pre-Virus Good Times, auto loans already exploded.

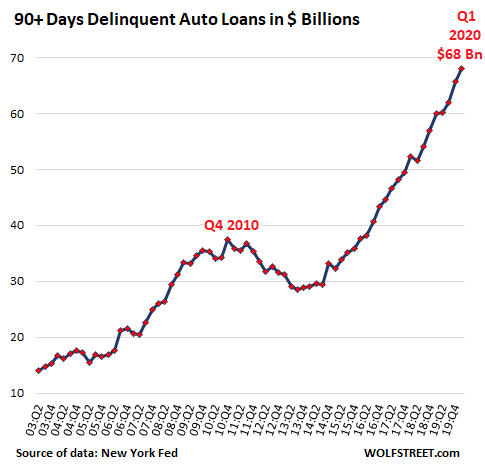

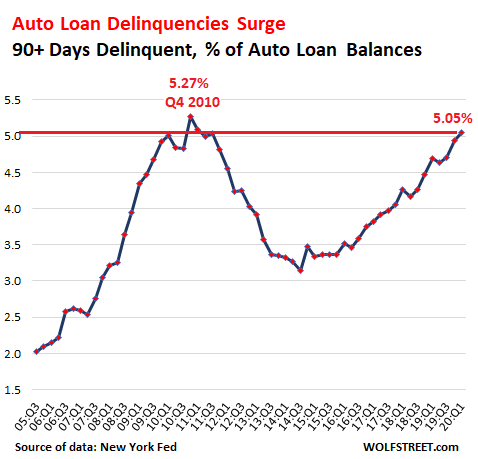

Serious delinquencies in auto loans and leases – those that are at least 90 days past due – surged by 13% in Q1 from a year ago to a historic high of $68 billion:

Delinquencies of auto loans to borrowers with prime credit ratings were near historic lows (0.27% in March), according to Fitch data. In the pre-Virus Good Times, it was the subprime loans – with credit scores below 620 – that were blowing up.

Seriously delinquent auto loans, at $68 billion, jumped to 5.05% of the $1.35 trillion in total auto loans and leases. This is only a notch below the peak of Financial Crisis 1 in Q4 of 2010 (when it was 5.27%), after General Motors and Chrysler had filed for bankruptcy as the industry was collapsing. But in Q1 2020, those were still the Good Times:

Delinquencies will now explode through the ceiling

In April, specialized subprime lenders started reporting surging delinquencies and plunging new business. Among the first was Credit Acceptance Corp [CACC] when it disclosed in an SEC filing on April 20 that it was getting hit due to the sudden job losses, as consumers were “delaying payments or re-allocating resources, leading to a significant decrease in our realized collections.”

It complained of a sudden drop in new business as consumer demand for vehicles fizzled. And this toxic mix of the surging delinquencies and dropping new business, it warned, “could cause a material adverse effect on our financial position, liquidity, and results of operations.”

Ally Financial [ALLY] disclosed on the same day in its Q1 earnings report that it had increased its provisions for loan losses by $504 million year-over-year “due to reserve build primarily driven by COVID-19 forecasted macroeconomic changes.”

During the analyst meeting, Ally CFO Jennifer LaClair said that about 25% of auto-loan borrowers had asked for a deferral of payment, and 18% had already enrolled in the program by the end of March 31. Ally allows auto-loan customers to defer payments for up to 120 days without late fee, but with finance charges accruing. This allows Ally to show the loans as current, rather than delinquent.

“We believe participation in this program will lower loss content,” LaClair told the analysts. “We will be able to track leading indicators of default and intervene early.”

Ally now also provides new auto loan borrowers who haven’t even made their first payment “the option to defer their first payment for 90 days without late fees being incurred but with finance charges accruing.”

These deferrals are not considered delinquencies. And it’s going to be tough to get a true sense as to who will still be making payments on their auto loans.

In mid-March, the world changed for subprime lenders. Delinquencies were already exploding in the Good Times, and now they’re in utter turmoil.

In addition, it is likely that prime loans are becoming delinquent as well, as many of these people too have lost their jobs – this includes dentists and other professionals with high incomes and big debts and lots of expenses and no savings, who’d suddenly had to close their operations, and their cash flow disappeared. If they fall behind on their debts, they’ll be subprime in a hurry.

In good times, subprime auto-loans are an immensely profitable business, with very high interest rates – often in the double digits – in a near-zero interest-rate environment.

The technologies for tracking the vehicles when it comes time to repossess them are effective; and a normally very liquid used-vehicle market via auctions around the country ensures that, normally, those repossessed vehicles are easy and quick to sell. There are losses and costs involved, but in good times, they’re more than compensated for by the big-fat interest rate margins the lenders make on all loans combined. And so the subprime lenders have gotten very aggressive since 2014. And for a while it worked.

Lenders have been able to securitize these loans and sell the asset-backed securities (ABS) into blistering demand from yield-chasing investors who have been bludgeoned by negative-interest-rate and low-interest-rate central-bank policies. Demand from those ABS investors fueled the subprime-auto-loan boom.

The Fed will try to force investors into a position where they feel they have to chase yield, and the Fed will try to create demand for these subprime auto loan ABS so that they don’t collapse.

But the normally liquid used-vehicle market isn’t that liquid anymore, as auction volume has plunged, and there is a flood of used-vehicle supply on the horizon from rental car companies trying to unload a big part of their now useless fleets, or creditors of rental-car companies taking possession of their collateral – the vehicles – and unloading them at the auctions, into very low demand.

This is a form of forced selling, and the whole industry is now afraid of it, and what it might do to wholesale prices. It will make it much harder for subprime auto lenders to dispose of their repos, and the losses will be greater, and there will be many more repos they’ll have to dispose of after all the deferrals run out and people cannot make their payments, and there won’t be enough new subprime lending business to cover up those losses.