BY JOHN MAULDIN

The experts who investigate transport disasters, crimes, and terror incidents usually create a chronology of events. Reading them in hindsight can be haunting—you know what’s coming and you want to scream, “Don’t do that!” But of course, it’s too late.

We do something similar in economics when we look back at past recession and market crashes. The causes seem obvious and we wonder why people didn’t see it at the time.

One of the examples today is a brewing crisis in the high-yield bond market. The problem is massive illiquidity. Trading can and will dry up in a heartbeat at the very time people want to sell.

Yet few investors are aware of that.

A Crisis in High-Yield Bonds

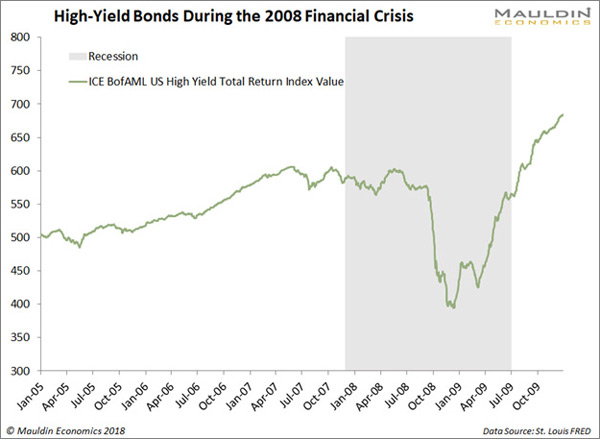

In late 2008, the high-yield bond benchmarks lost a third of their value within a few weeks, and many individual bond issues lost much more. In large part, that’s because buyers disappeared.

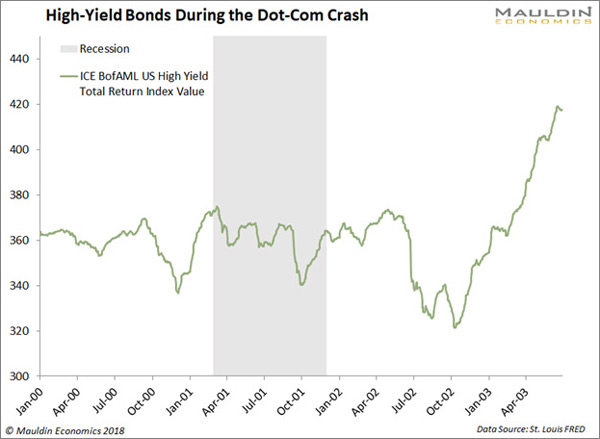

The same thing happened in the dot-com recession, though not quite as dramatically. There were still several whipsaws and a particularly terrible month in June 2002.

This time, I believe the collapse will go deeper and happen faster because Dodd-Frank has decimated the market makers’ ability to cushion it. Likewise, the Fed will be reluctant to bail out ridiculously priced bonds like WeWork and its many covenant-lite, unsecured brethren. And rightly so, in my view.

But if it’s not high yield, something else will set off the fireworks.

The Beginning of Woes

Remember, then-Fed Chair Ben Bernanke said in 2007 that the subprime debt problem was “contained.” Whatever starts the next credit crisis, authorities will assure us it is “contained.” (Spoiler: It won’t be.)

Last week, I read a powerful chapter by my friend William White, former chief economist for the Bank of International Settlements and now chairman for the OECD economic committee.

I read everything from Bill that I can get my hands on. He is my favorite central banker in the world. This paragraph jumped out at me (emphasis mine):

… the trigger for a crisis could be anything if the system as a whole is unstable. Moreover, the size of the trigger event need not bear any relation to the systemic outcome. The lesson is that policymakers should be focused less on identifying potential triggers than on identifying signs of potential instability.

This implies that paying attention to macroeconomic “imbalances” may pay bigger dividends than trying to assess financial instability through highly disaggregated “risk maps” of the sort currently being encouraged by the G20 and the IMF. The latter are not only expensive to monitor, but potential rupture points in the financial fabric can change rapidly in real time.

Perhaps more important, serious economic and financial crises can have their roots in imbalances outside the financial system.

The bottom line: the system itself is unstable. Predicting the actual trigger in advance is difficult. I can imagine numerous possible “triggers” for the coming credit crisis.

As in the biblical book of Revelation, the initial credit crisis stemming from the fall of high-yield bonds will be merely the beginning of woes. Illiquidity will spread as lower-end corporate bonds fall to junk ratings.

Legal and contractual constraints will then force institutions to sell, pressuring all except the highest-grade corporate and sovereign bonds. Treasury and prime-rated corporate bond yields will go down, not up (see 2008 for reference on this).

The selling will spill over into stocks and trigger a real bear market—much worse than the hiccups we saw earlier this year.

I give the probability of the credit crisis in the high-yield junk bond market somewhere close to 95%. For the record, nothing is 100% certain, as we don’t know the future.

But I think this is pretty much baked in the cake.