By John Mauldin

Here’s a quote from my friend Peter Boockvar that has drawn an enormous amount of interest:“We no longer have business cycles, we have credit cycles.”

Let’s cut that small but meaty sound bite into pieces. What do we mean by “business cycle,” exactly? Well, it looks something like this.

A growing economy peaks, contracts to a trough (what we call “recession”), recovers to enter prosperity, and hits a higher peak. Then the process repeats.

The economy is always in either expansion or contraction. However, this pattern broke down in the last decade.

Low Rates to Blame

In the 2008 financial crisis, we had an especially painful contraction. It was followed by an extraordinarily weak expansion.

GDP growth should reach 5% in the recovery and prosperity phases, not the 3% we have seen since 2008.

Peter blames the Federal Reserve’s artificially low interest rates. Here’s how he put it in one of his letters:

To me, it is a very simple message being sent. We must understand that we no longer have economic cycles. We have credit cycles that ebb and flow with monetary policy. After all, when the Fed cuts rates to extremes, its only function is to encourage the rest of us to borrow a lot of money and we seem to have been very good at that. Thus, in reverse, when rates are being raised, when liquidity rolls away, it discourages us from taking on more debt. We don’t save enough.

The problem is that, over time, debt stops stimulating growth. Debt-fueled growth is fun at first but simply pulls forward future spending.

Debt also boosts asset prices. That’s why stocks and real estate have performed so well. If financing costs rise and buyers lack cash, the asset price must fall. And fall it will.

Since debt drives so much GDP growth, its cost (i.e., interest rates) is the main variable defining where we are in the cycle.

The Fed controls that cost, so we all obsess on Fed policy. And rightly so.

Game Changer

In an old-style economic cycle, recessions triggered bear markets. Economic contraction slowed consumer spending, corporate earnings fell, and stock prices dropped.

That’s not how it works when the credit cycle is in control.

In a credit-driven economy, recessions don’t cause lower prices. It’s lower prices that cause recession. That’s because access to credit drives consumer spending and business investment.

Take it away and they decline. Recession follows.

If some of this sounds like the Hyman Minsky financial instability hypothesis, you’re exactly right. Minsky said exuberant firms take on too much debt, which paralyzes them, and then bad things start happening.

I think we’re approaching that point.

Credit-Cycle Peak

The last “Minsky Moment” came from subprime mortgages.

Those are getting problematic again, but I think today’s bigger risk is corporate debt, especially high-yield bonds.

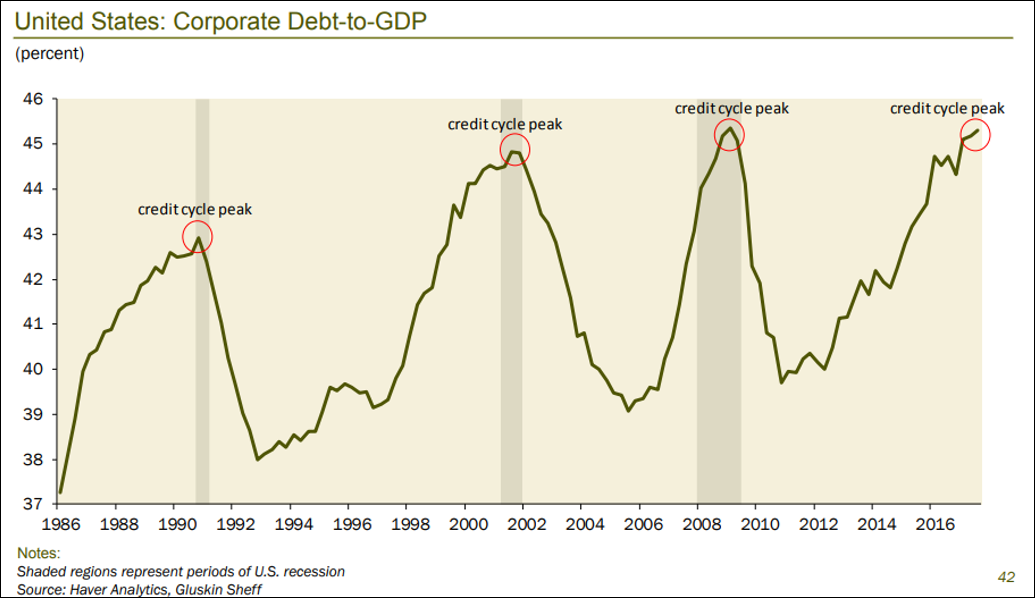

Corporate debt is now at a level that has not ended well in past cycles. Here’s a chart from Dave Rosenberg of Gluskin Sheff:

Source: Gluskin Sheff

The debt/GDP ratio could go higher still, but I think not much more. Whenever it falls, lenders (including bond fund and ETF investors) will want to sell.

Then comes the hard part: to whom?

Unprecedented Liquidity Crisis

You see, it’s not just borrowers who’ve gotten used to easy credit. Many lenders assume they can exit at a moment’s notice.

We have two related problems here:

- Corporate debt issuance, especially high-yield debt, has exploded since 2009.

- Tighter regulations discouraged banks from making markets in corporate and high-yield debt.

Both are problems, but the second is worse. Experts tell me that Dodd-Frank requirements have reduced major banks’ market-making abilities by around 90%.

For now, bond market liquidity is fine because hedge funds and other non-bank lenders have filled the gap.

The problem is they are not true market makers. Nothing requires them to hold inventory or to buy when you want to sell.

That means all the bids can “magically” disappear just when you need them most.

In a bear market, you sell what you can, not what you want to. The picture will not be pretty.

To make matters worse, many of these lenders are far more leveraged this time. They bought their corporate bonds with borrowed money. They were confident that low interest rates and defaults would keep risks manageable.

In fact, according to S&P Global Market Watch, 77% of corporate bonds that are leveraged are what’s known as “covenant-lite.”

Put simply, the borrower doesn’t have to repay by conventional means. Sometimes they can even force the lender to take on more debt.

As the economy enters recession, many companies will lose their ability to service debt. Normally, this would be the borrowers’ problem, but covenant-lite lenders took it on themselves.

Another problem is that much of the at least $2 trillion in bond ETF and mutual funds isn’t owned by long-term investors who hold to maturity.

When the herd of investors calls up to redeem, there will be no bids for the “bad” bonds. But funds are required to pay redemptions, so they’ll have to sell their “good” bonds.

Remaining investors will be stuck with an increasingly poor-quality portfolio, which will drop even faster.

Those of us with a little gray hair have seen this before, but I think the coming crisis is biblical in proportion.