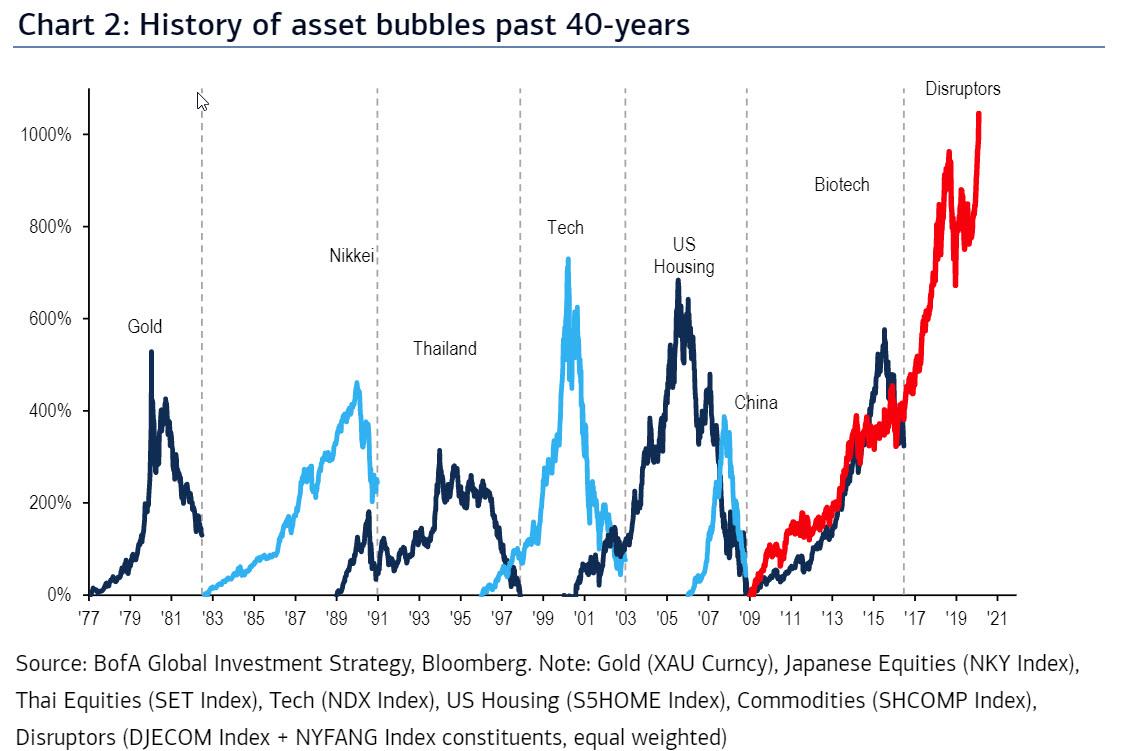

Trump and Federal Reserve are pumping up the stock market non-stop, speculative sentiment is now out of control. At some point this market will collapse.

The Mississippi Bubble of 1718-1720

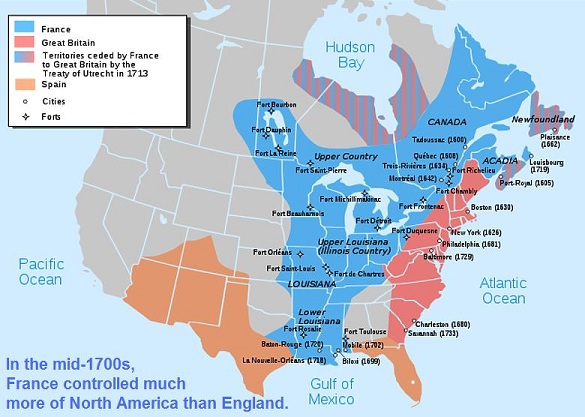

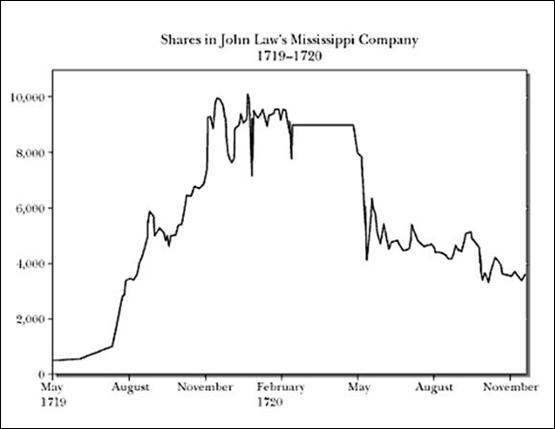

The Mississippi Bubble was an economic bubble in France in the early 1700s that developed in parallel with Britain’s disastrous South Sea Bubble. The mastermind behind the Mississippi Bubble was John Law, a Scottish financier, gambler and playboy who ascended into the upper echelons of French public finance through his friendship with the Duke of Orléans. Law became the French government’s primary financial advisor and used this power to establish the Banque Générale, a bank with the authority to issue “paper” money, as well as the Mississippi Company (later called “the Compagnie des Indes”), which was granted a monopoly on the development of France’s vast Mississippi Territory in North America. When investors started salivating over the supposedly immense bounty of resources in the Mississippi Territory, including gold and silver, they bid Compagnie des Indes shares up to astronomical heights. Unfortunately, the company’s prospects turned out to be little more than empty promises and the shares crashed back down to earth, taking down France’s stock market and public finances with it.

John Law hailed from Fife, Scotland, where he was born into an affluent family of bankers and goldsmiths. Law became his father’s apprentice at age fourteen and studied the banking business until his father’s death three years later. Soon after, Law travelled to London in pursuit of adventure and earned a living as a gambler thanks to his keen mathematical abilities. In London, the twenty-three year old Law became involved in a duel over a lady friend in which he swiftly killed his opponent and was charged with murder and sentenced to death. John Law spent a brief time in prison before he escaped to mainland Europe, where he studied high finance in cities such as Amsterdam, Venice and Genoa. In 1705, Law published an academic paper in which he argued against the use of precious-metal backed currency in favor of “paper” or fiat currency, claiming that the use of fiat currency would stimulate commerce (Smant, 2001). Due to these distinct views, Law is often considered to be an early Keynesian-style economist.

John Law hailed from Fife, Scotland, where he was born into an affluent family of bankers and goldsmiths. Law became his father’s apprentice at age fourteen and studied the banking business until his father’s death three years later. Soon after, Law travelled to London in pursuit of adventure and earned a living as a gambler thanks to his keen mathematical abilities. In London, the twenty-three year old Law became involved in a duel over a lady friend in which he swiftly killed his opponent and was charged with murder and sentenced to death. John Law spent a brief time in prison before he escaped to mainland Europe, where he studied high finance in cities such as Amsterdam, Venice and Genoa. In 1705, Law published an academic paper in which he argued against the use of precious-metal backed currency in favor of “paper” or fiat currency, claiming that the use of fiat currency would stimulate commerce (Smant, 2001). Due to these distinct views, Law is often considered to be an early Keynesian-style economist.

When the desperate Duke of Orléans came looking to John Law for help, Law viewed it as an opportunity to put his monetary theory into action. In 1716, Law received the French government’s permission to establish a national bank, the Banque Générale, which took in deposits of gold and silver and issued “paper” bank notes in return. The bank notes issued by Banque Générale were not legal tender but were accepted as such by the French public because they were redeemable in official French currency. Banque Générale built up its bank reserves through the issuance of stock and from profits earned through the management of the French government’s finances.

Explosive demand for Compagnie des Indes shares caused the total amount of “paper” money bank notes in circulation to increase 186% in one year due to the fact that Banque Générale issued as much bank notes as the public demanded. This expansion of the money supply resulted in a powerful inflationary episode in which the price of goods doubled between July 1719 and December 1720. A good portion of Compagnie des Indes share price gains were due to this inflation as well (Smant, 2001). Paris experienced a “bubble economy”-type boom as real estate prices and rents soared twenty-fold and wealthy speculators clamored to buy luxury goods (Sebastian, 2011). According to Charles Mackay, “New houses were built in every direction, and an illusory prosperity shone over the land, and so dazzled the eyes of the whole nation, that none could see the dark cloud on the horizon announcing the storm that was too rapidly approaching.”

Soon, Banque Générale had issued vast quantities of bank notes even though they did not have an equivalent amount of gold and silver-based legal tender for everyone who eventually wished to redeem their notes. It is likely that John Law had expected to fulfill Banque Générale’s precious metals deficit with gold and silver imported from North America by the Compagnie des Indes.

The combination of aggressive investor selling and Law’s devaluations caused Compagnie des Indes shares to collapse from 10,000 livres to 1,000 livres by December 1720 (Moen, 2001). Compagnie investors were financially-ruined and many former millionaires became paupers. By the end of 1720, John Law was viewed as a scam artist and his rivals were given control over two-thirds of his companies’ shares. Share prices further deflated to 500 livres in 1721 (Moen, 2001). Soon after, John Law escaped France, disguised as a woman for his own safety, and spent the rest of his life as an impoverished gambler in various parts of Europe. The collapse of Banque Générale and the Compagnie des Indes, which coincided with the popping of Britain’s South Sea Bubble, plunged France and other European countries into a severe economic depression and laid the groundwork for the French Revolution that occurred later on in the century.

Although traditionally considered a bubble, the Mississippi Bubble wasn’t actually a bubble, in a precise technical sense. A bubble is primarily caused by widespread mania and speculation, followed by a brutal collapse in asset values. In contrast, the Mississippi Bubble was the result of failed monetary policies that caused excessive money supply growth and inflation.

U.S. Stock Market Bubble 2020

fed, wall street, & trump juicing stocks to record highs on the lack of fundamentals with no recovery in the economy but rather deceleration could lead to blowoff top pic.twitter.com/auXhBcezly

— Alastair Williamson (@StockBoardAsset) February 22, 2020

Let me see if I have this straight – the White House is looking for ways to get Americans to pump even more money into stocks when valuations are second only to the highs seen just before the tech bubble burst? pic.twitter.com/lUb8Z1Cdbd

— Robert Burgess (@BobOnMarkets) February 14, 2020

Leaking this on a week where US household debt jumped by the most in 12 years is 😚 https://t.co/pQtxv4Mcqw https://t.co/qLDSYyIXi3

— Carl Quintanilla (@carlquintanilla) February 14, 2020

if only there were signs of investors chasing yield😴💤@RobSKaplan @RaphaelBostic @marydalyecon @EricRosengren @neelkashkari https://t.co/TJhb2zPJkg

— M/I_Investments (@MI_Investments) February 14, 2020

Stocks: All-Time Highs

Bonds: All-Time Highs

Real Estate: All-Time Highs

Economy: Longest Expansion in History (127 months)

Fed: Expected to Cut Rates for 4th Time in July, Growing its Balance Sheet $75 billion/month since last October pic.twitter.com/ycKNZjOlES— Charlie Bilello (@charliebilello) February 14, 2020

Congress should ask the Fed why they indirectly bought over $500 BILLION in stocks in the last 4 months ($180 through repo market and $300 through NotQE) @RepMaxineWaters @HouseDemocrats https://t.co/I31DT1jboR

— Thomas Kaine (@thomaskaine5) February 11, 2020

Here It Is: One Bank Finally Explains How The Fed's Balance Sheet Expansion Pushes Stocks Higher https://t.co/Wqc0yCPjca pic.twitter.com/VDjbXRdXCx

— Zero Hedge News (@RssZero) February 7, 2020

Trump's gives $1trillion tax break to corporations.

Corporations use money to buy back stock.

Share prices and Dow rise.

Income remains stagnant.

Employment remains stagnant.

Where did that money come from?

How much federal tax do those companies pay?

Who paid for the tax cut?— Joseph (@jowey2k) February 6, 2020

https://twitter.com/search?q=trump%20tweets%20stocks&src=typed_query

Capital gains tax should be 0%. https://t.co/qrfCotpFpi

— Lawrence Hamtil (@lhamtil) February 14, 2020

Just to put things into perspective: Central banks around the world keep the printing press rumbling. pic.twitter.com/6C7OG4qkRO

— Holger Zschaepitz (@Schuldensuehner) February 14, 2020

(maybe because the Top 20% got all the gains and the bottom 80% didn't). IQ of 5 would have figured this out

"Powell says Fed will aggressively use QE to fight next recession"

About as tone deaf as it gets.@RobSKaplan @marydalyecon @RaphaelBostic @EricRosengren @neelkashkari pic.twitter.com/zjnH7BQQ8Z

— M/I_Investments (@MI_Investments) February 14, 2020

OPINION: Tesla's stock is in a bubble. It is going to crash. https://t.co/q1iaXxZTCg

— MarketWatch (@MarketWatch) February 15, 2020

“Speculative Energy in the Market is Incredibly out of Control”

“It is a mind-numbing exercise for investors who see the cognitive dissonance”: CIO at Guggenheim Partners.

This market has been an astounding experience for people who’ve traded through the prior stock market bubbles and the last three crashes, who’ve seen a national and several regional housing bubbles form and implode, who’ve seen the subprime-auto-loan Asset Backed Securities bubble blow up in the mid-1990s and again during the Financial Crisis, and now it’s starting to head the same direction again. But no one can remember ever having seen markets like these that have formed the Everything Bubble.

It’s a phenomenon where nearly all asset prices are inflated. It’s not a secret. There are signs all over the place. Yesterday, the government sold 30-year bonds at a yield of 2.06%, below the rate of inflation as measured by CPI (2.5%). The Fed is fixated on driving inflation higher. But to beat the current CPI with a little bit of a margin that might evaporate over the next few months, you have to take fairly big risks and go to the low-end of investment-grade corporate bonds, to BBB-rated bonds, which are just above junk bonds (here is my plain-English cheat sheet for the corporate credit rating scales), and their average yield is 2.96%.

Earnings growth has been lousy, for the companies that even have earnings. And one issue after another comes along, and markets just continue to inflate, and markets that normally balance each other out, with one going up while the other is going down, such as the bond market and the stock market, have been going up in lockstep.

Stock Market had another good day but, now that the Tax Cut Bill has passed, we have tremendous upward potential. Dow just short of 25,000, a number that few thought would be possible this soon into my administration. Also, unemployment went down to 4.1%. Only getting better!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) January 4, 2018

I am at Camp David working on many things, including Iran! We have a great Economy, Tariffs have been very helpful both with respect to the huge Dollars coming IN, & on helping to make good Trade Deals. The Dow heading to BEST June in 80 years! Stock Market BEST June in 50 years!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) June 22, 2019

Trump tweets support for negative interest rates

Stock Market had another good day but, now that the Tax Cut Bill has passed, we have tremendous upward potential. Dow just short of 25,000, a number that few thought would be possible this soon into my administration. Also, unemployment went down to 4.1%. Only getting better!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) January 4, 2018

We’re Witnessing The Biggest Asset Bubble Ever Created By A Central Bank

BofA: “Mexican central bank makes it 800 interest rate cuts since Lehman bankruptcy…”