Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

For the past two months, the sound of wailing and gnashing of teeth about the Fed’s QE unwind has been deafening. The Fed started the QE unwind in October 2017. As I covered it on a monthly basis, my ruminations on how it would unwind part of the asset-price inflation and Bernanke’s “wealth effect” that had resulted from QE were frequently pooh-poohed. They said that the truly glacial pace of the QE unwind was too slow to make any difference; that QE had just been a “book-keeping entry,” and that therefore the QE unwind would also be just a book-keeping entry; that QE had never caused any kind of asset price inflation in the first place, and that therefore the QE unwind would not reverse that asset-price inflation, or whatever.

But in October last year, when all kinds of markets started reversing this asset price inflation, suddenly, the QE unwind got blamed, and the Fed – particularly Fed Chairman Jerome Powell – has been put under intense pressure to cut it out. Yet it continues:

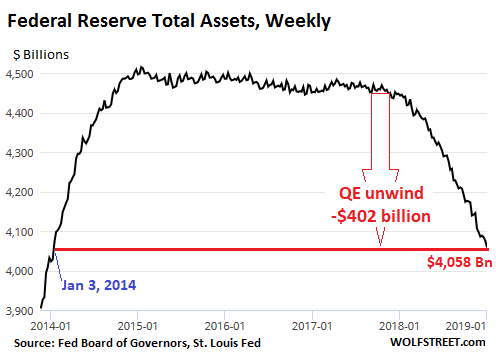

The Fed shed $28 billion in assets over the four weekly balance-sheet periods of December. This reduced the assets on its balance sheet to $4,058 billion, the lowest since January 08, 2014, according to the Fed’s balance sheet for the week ended January 3. Since the beginning of this “balance sheet normalization,” the Fed has now shed $402 billion.

According to the Fed’s plan released when the QE unwind was introduced, the Fed is scheduled to shed “up to” $30 billion in Treasuries and “up to” $20 billion in MBS a month – now that the QE unwind has reached cruising speed – for a total of “up to” $50 billion a month. So how did it go in December?

Treasury Securities

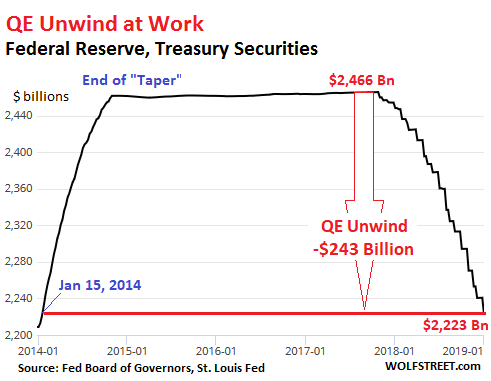

Over the four weeks from December 6 through January 3, the Fed’s holdings of Treasury securities fell by $18 billion to $2,223 billion, the lowest since January 15, 2014. Since the beginning of the QE-Unwind, the Fed has shed $243 billion in Treasury securities:

The Fed sheds Treasury securities not by selling them but by allowing them to “roll off” without replacement when they mature. When Treasury securities mature, the Treasury Department transfers money in the amount of face value plus any outstanding interest to all holders of those securities. The fact that Treasuries mature mid-month or at the end of the month creates the step-pattern of the QE unwind in the chart above.

On December 15, no Treasuries in the Fed’s portfolio matured. On December 31, three issues matured, totaling $18 billion. This did not reach the cap of $30 billion. So for the month, all $18 billion in Treasury securities that matured were allowed to roll off without replacement. And the Treasury Department paid the Fed for them.

The Fed creates money, and it destroys money; but it doesn’t hold trillions of dollars in cash. So when it received the $18 billion from the Treasury Department, it destroyed them just as it had created them to purchase these securities during QE.

For those wailing and gnashing their teeth about the QE unwind: Going forward, there will not be all that many months when enough Treasuries mature to reach the cap of $30 billion. For example, in January the Fed’s maturity schedule shows that four bond issues will mature totaling only $13.3 billion, including one issue of TIPS.

Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS)

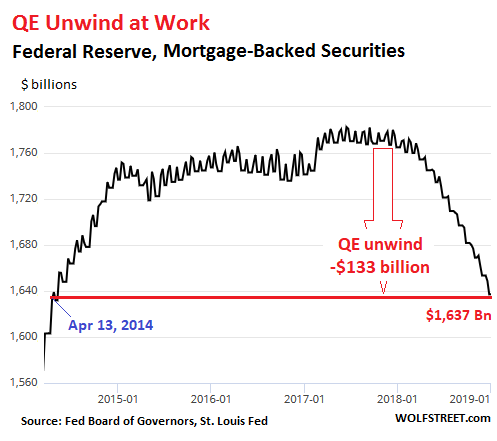

The residential MBS that the Fed acquired as part of QE were issued and guaranteed by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae. Holders of these MBS receive principal payments as the underlying mortgages are paid down or are paid off. The remaining principal is paid off at maturity. To keep the balance of MBS from declining after QE had ended, the New York Fed’s Open Market Operations continued purchasing MBS in the market.

The Fed books MBS trades at settlement, which lags the trade by two to three months. Due to this lag, the amount of MBS on the weekly balance sheets in December reflected trades in September and October. In September, which was the last month of the ramp-up period, the cap for shedding MBS was $16 billion. In October, the cap rose to $20 billion.

In December, the balance of MBS fell by $16 billion, to $1,653 billion, back where it had been on April 13, 2014. Since the beginning of the QE unwind, the Fed has shed $133 billion in MBS:

So December was a somewhat slow month for the QE unwind, with $18 billion in Treasury securities and $16 billion in MBS rolling off the balance sheet, for a total of $34 billion that went back where it had come from during QE – namely ambient air.