Airlines don’t expect a quick recovery back to “normal” either. Based on their decisions about aircraft in their fleets, they expect this to drag out for years.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

This was the first big travel weekend of the Pandemic Era – meaning a holiday weekend when normally Americans like to go somewhere. So let’s see how it went for airlines.

The worst for the economy may be over, meaning that the economy, which is in terrible shape, may not get worse from here on forward, and that activity is ticking up, though the economic data that lag by weeks and months, such as unemployment rates, consumer spending, or GDP, are certainly going to get a lot worse because they’re still trying to catch up with just how bad it already is.

In the immediate near-real-time data, such as passenger air traffic, measured by the TSA’s daily checkpoint screenings at airports around the US, we can see that the economy is getting better – in micro-steps.

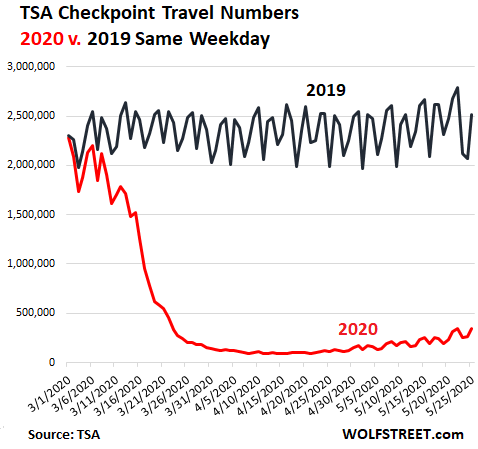

These TSA screenings show: One, how bad it has gotten for the travel industry; two, that activity is picking up only a tiny bit when looking at the whole scene; three, that activity remains so deep in the tank that the tiny uptick, when looked at without magnifying glass, can barely be seen; and four, that this recovery is going to be slow and take a long time.

The TSA reported this morning that on Monday, Memorial Day, checkpoint screenings at US airports reached 340,769. On Friday, the total screenings had reached 348,673, the highest since lockdowns started, and more than triple the 95,000-range in mid-April. When something shoots up 265% in six weeks, as the TSA checkpoint screenings have done, that’s encouraging.

However, this weekend’s screenings remained minuscule and abysmally low. Last year on Friday, TSA screenings reached 2,792,670, the highest in the March-May period. And Monday last year, the screenings reached 2,512,237. Compare those figures (black line) to this year’s screenings (red line), and note the seasonal increase in both:

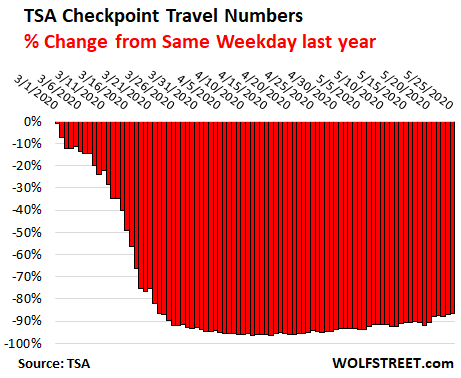

On Friday, TSA screenings were down 87.5% from Friday a year ago. On Memorial Day this year, screenings were down 86.4% from Monday a year ago. You can see the improvement: The number of screenings at the low point in April were down about 95% from a year ago:

So there is an increase in passenger travel from the near-zero levels of early April – hence the “recovery” – but travel is still minuscule compared to a year ago.

And US airlines are not expecting an instant V-shaped recovery either. In this environment, airlines reacted the only way they could: They engaged in drastic short-term culling of capacity, and they’re making big long-term adjustments to their fleets to deal with this situation over the long term.

All airlines cut capacity by removing flights from their schedule and by parking planes. United cut its capacity by 90% in April and has since been lambasted publicly for packing people into full planes, ignoring any notion of social distancing. I analyzed this phenomenon in a comment at the time:

“The idea is to pack them sardines into them cans, and if you don’t have enough of them sardines for them cans, you still pack them into them cans, but use fewer of them cans.”

And that’s what airlines are doing. In April, the IATA reported that “Almost 10,500 aircraft, representing 40% of the global fleet, have been grounded already and that number is only likely to increase.” These are the airlines’ instant and short-term reactions to the crisis.

But airlines have also been making long-term decisions: Retiring planes in large numbers much earlier than anticipated.

Delta, for example, said that as of mid-May, it has “parked more than 650 mainline and regional aircraft to adjust capacity to match reduced customer demand.” And it announced that it would retire all its 18 Boeing 777 by the end of this year. These planes entered the fleet between 1999 and 2008. “The retirement will accelerate the airline’s strategy to simplify and modernize its fleet, while continuing to operate newer, more cost-efficient aircraft,” it said.

In April, Delta had announced that it would accelerate the retirement of its MD-88 and MD-90 (“Why are they still in the fleet,” says me, Delta Frequent Flyer, every time I get on this museum piece). Final flights will be on June 2.

American Airlines announced that it would retire its fleet of Boeing 767, Boeing 757, Airbus A330-300, Embraer 190, Embraer 140, and Bombardier CRJ200. Since these retirements were “earlier than previously planned as a result of the decline in demand for travel due to COVID-19,” American Airlines said, they triggered write-downs of over $1 billion.

Airline after airline is using the collapse in demand to sort through its fleet and to get rid of the least efficient and costliest planes to operate. These moves – as American Airlines has shown – are costly in the short term because equipment with a book value is being written off, triggering a hit to earnings. Retiring these planes earlier than previously planned can also trigger labor contract expenses.

Decisions about what aircraft should be in the fleet, and what aircraft should exit the fleet, are long-term decisions. And they indicate clearer than anything else that airlines don’t expect a quick recovery back to “normal,” that they expect this to drag out for years. After 9-11, it took nearly four years for operating revenues of US airlines to get back to pre-9-11 levels. After the Financial Crisis, it took nearly three years. And for the airlines, and for potential passengers, this crisis is far bigger than the prior two crises.