Wolf Richter wolfstreet.com, www.amazon.com/author/wolfrichter

Companies buying back their own shares has “consistently been the largest source of US equity demand.” Without them, “demand for shares would fall dramatically.” Too painful to even imagine.

Goldman Sachs asked a nerve-racking question and came up with an equally nerve-racking answer: What would happen to stocks “in a world without buybacks.” Because buybacks are a huge deal.

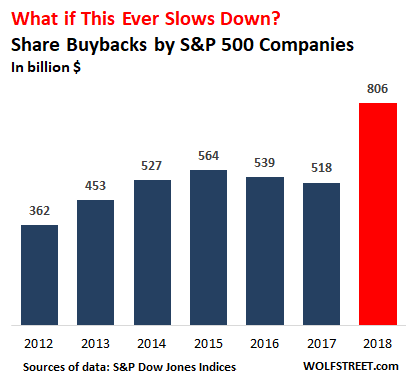

In the fourth quarter 2018, share repurchases soared 62.8% from a year earlier to a record $223 billion, beating the prior quarterly record set in the third quarter last year, of $204 billion, according to S&P Dow Jones Indices on March 25. It was the fourth quarterly record in a row, the longest such streak in the 20 years of the data. For the whole year 2018, share buybacks soared 55% year-over-year to a record $806 billion, beating the prior record of $589 billion set in 2007 by a blistering 37%!

Share buybacks had already peaked in 2015 and ticked down in 2016 and 2017. Then the tax reform act became effective on January 1, 2018, and share buybacks skyrocketed.

The record buybacks in Q4 came even as stock prices declined on average 5.3%, according to S&P Down Jones Indices. On some bad days during the quarter, corporations were about the only ones left buying their shares.

For the year 2018, these were the top super-duper buyback queens:

- Apple: $74.2 billion

- Oracle: $29.3 billion

- Wells Fargo $21.0 billion

- Microsoft: $16.3 billion

- Merck: $9.1 billion

But who, outside of corporations buying back their own shares, was buying shares? Goldman Sachs strategists answered this question in a report cited by Bloomberg, that used data from the Federal Reserve to determine “net US equity demand.” These are the largest investor categories other than corporate buybacks, five-year totals:

- Foreign investors shed $234 billion.

- Pension funds shed $901 billion, possibly to keep asset-class allocations on target as share prices soared.

- Stock mutual funds shed $217 billion.

- Life insurers added 61 billion

- Households added $223 billion.

The net effect of these investor groups is that they together shed $1.1 trillion of shares (included in these categories, and spread over them, are ETFs). But the $1.1 trillion of shares that these investor groups shed over those five years was overpowered by $2.95 trillion of share buybacks over those five years.

So it all worked out. As investors were selling, companies were buying back their own shares. And markets boomed. But what would happen to stocks in a “world without buybacks?”

Share buybacks were considered securities fraud under most conditions until 1982 but then became legal under a new set of loose rules. Now some folks in Congress from both parties, who are worried about corporate governance and the like, have targeted share buybacks in some of their speeches and have proposed some legislation. Goldman is apparently worried that they might get some traction. And so it created its scenario of a world without buybacks.

It would be a truly unspeakably, nay, unthinkably gruesome nightmare that no politician would want to be responsible for: a world in which stock prices would decline!

“Repurchases have consistently been the largest source of U.S. equity demand,” the Goldman strategists wrote in their note. “Without company buybacks, demand for shares would fall dramatically.”

Volatility would rise. To figure this out, the strategists looked at 25 years of quarterly blackout periods that restrict some buybacks around earnings release dates. These blackout periods start five weeks before earnings releases and last until two days afterwards. But they’re not blackout periods: They restrict only spur-of-the-moment buybacks. Scheduled buybacks around earnings release dates are not restricted (my discussion of the rules governing buybacks and blackout periods).

By looking at stock performance during those blackout periods, the strategists discovered that, according to Bloomberg, “return dispersion and volatility during blackout windows have been higher compared with non-blackout periods: 16 percentage points versus 14 percentage points, and 16.4 points versus 15.8 points, respectively.”

In addition, earnings-per-share would dwindle. Share buybacks reduce the number of shares outstanding, and total earnings divided by fewer shares outstanding gives a larger earnings-per-share number. But without share buybacks, earnings-per-share growth and actual earnings growth would be the same. That would be devastating.

They note that over the past 15 years, for the median S&P 500 company, earnings-per-share growth, powered by the reduction in the stock outstanding, was on average 2.6 percentage points higher than actual earnings growth.

In this manner, in a world without buybacks, “forward EPS growth could be trimmed by 250 basis points,” they said. This type of reduction, they said, has historically corresponded to a 1-point decline in forward price-earnings multiples.” In other words, valuations would fall.

And then there is the biggie: The question of just “demand,” no matter what earnings or earnings-per-share may be.

“Eliminating the largest source of equity demand could lower the demand curve if other investor categories do not replace the corporate bid from buybacks,” they warned. And the bull market would lose the force that powered it.

Share buybacks are the relentless bid, buying at any price, buying not to acquire assets at a low price but buying with the specific purpose of pushing up prices.

Letting the stock market fend for itself and embark on its own price discovery without the relentless bid of share buybacks would be a true nightmare. No one would be ready for it. This type of world is just too painful to even imagine these days.