Just a couple of weeks ago the financial world’s biggest worry was the plunging price of oil. Supply was up, stockpiles were building and speculation was pointing towards $40 a barrel, a price at which the fracking/shale oil “miracle” would evaporate. A trillion dollars of related junk debt would default, taking a big part of the leveraged speculating community along for the ride.

Then it all changed. Someone attacked some ships and oil infrastructure in the Middle East, the US and Saudi Arabia accused Iran, and now the fear is that a major regional war will interrupt the flow of oil, sending its price way up and causing a financial crisis at least as severe as a shale oil debt collapse.

This is a legitimate concern, for two reasons.

First, oil shocks have happened in the past, most notably during the Arab-Israeli war of the 1970s. So we know what they do, and it isn’t pretty. Gas prices jump, workers can’t afford their commute, the economy slows dramatically and pretty much everyone other than domestic energy companies suffers badly.

Second and potentially more serious, the pretext for this war is so blatantly false that it risks destroying what little creditability the US government has left. Think about it: With the US doing everything it can to delegitimize and destabilize Iran while positioning assets for an invasion, Iran’s leaders … start attacking oil tankers in its offshore waters.

Does that make sense? Of course not. Much more likely is that this is yet another false flag – that is, an incident faked to give a pretext for war – and a clumsy one at that.

For readers who aren’t clear on the false flag concept and its ubiquity in geopolitics, here are just a few of the dozens of documented examples:

- Japanese troops blew up a train track in 1931, blamed it on China and used it to justify the invasion of Manchuria.

- After taking power, the Nazis burned down their own parliament building and blamed the communists. Later on, they faked attacks on German citizens and blamed the Poles, to justify the subsequent invasion of that country.

- In 1939 the Soviets shelled one of their own villages and blamed Finland, prior to invading.

- In 1954 Israeli terrorist cells operating in Egypt bombed U.S. diplomatic facilities, leaving behind evidence implicating Arabs.

- The CIA hired Iranians in the 1950s to pose as Communists and stage bombings in Iran in order to ignite a rebellion against the democratically-elected government. After the rebellion succeeded the US installed a hand-picked dictator.

- The US staged a naval engagement — the Gulf of Tonkin incident – and blamed the North Vietnamese, providing a pretext for entering the Vietnam War.

- The FBI used provocateurs in the 1950s through 1970s to carry out violent acts and falsely blame them on political activists.

- In 1984, Israel faked radio messages that linked Lybia to terrorism. The US bombed Libya immediately thereafter.

- Russian blew up apartment buildings in 1999 and falsely blamed it on Chechens, in order to justify an invasion of Chechnya

The list goes on seemly forever. But these examples are enough to make the twin points that 1) lots of countries employ false flags attacks, and 2) the US is especially fond of them.

There’s just one problem this time: Everyone is on to it. Even the New York Times, which has never met a Mid East war it didn’t love, sees through the deception:

As Trump Accuses Iran, He Has One Problem: His Own Credibility

To President Trump, the question of culpability in the explosions that crippled two oil tankers in the Gulf of Oman is no question at all. “It’s probably got essentially Iran written all over it,” he declared on Friday.

The question is whether the writing is clear to everyone else. For any president, accusing another country of an act of war presents an enormous challenge to overcome skepticism at home and abroad. But for a president known for falsehoods and crisis-churning bombast, the test of credibility appears far more daunting.

For two and a half years in office, Mr. Trump has spun out so many misleading or untrue statements about himself, his enemies, his policies, his politics, his family, his personal story, his finances and his interactions with staff that even his own former communications director once said “he’s a liar” and many Americans long ago concluded that he cannot be trusted.

Fact-checking Mr. Trump is a full-time occupation in Washington, and in no other circumstance is faith in a president’s word as vital as in matters of war and peace. The public grew cynical about presidents and intelligence after George W. Bush’s invasion of Iraq based on false accusations of weapons of mass destruction, and the doubt spilled over to Barack Obama when he accused Syria of gassing its own people. As Mr. Trump confronts Iran, he carries the burden of their history and his own.

“The problem is twofold for them,” said John E. McLaughlin, a deputy C.I.A. director during the Iraq war. “One is people will always rightly question intelligence because it’s not an exact science. But the most important problem for them is their own credibility and contradictions.”

The task is all the more formidable for Mr. Trump, who himself has assailed the reliability of America’s intelligence agencies and even the intelligence chiefs he appointed, suggesting they could not be believed when their conclusions have not fit his worldview.

All of that can raise questions when international tension flares up, like the explosion of the two oil tankers on Thursday, a provocation that fueled anxiety about the world’s most important oil shipping route and the prospect of escalation into military conflict. When Mr. Trump told Fox News on Friday that “Iran did do it,” he was asking his country to accept his word.

“Trump’s credibility is about as solid as a snake oil salesman,” said Jen Psaki, who was the White House communications director and top State Department spokeswoman under Mr. Obama. “That may work for selling his particular brand to his political base, but during serious times, it leaves him without a wealth of good will and trust from the public that what he is saying is true even on an issue as serious as Iran’s complicity in the tanker explosions.”

Combine these two problems – a Middle East war sending oil much higher, and a near-universal lack of belief in the rationale for that war – and the remaining faith in American competence and honesty might evaporate.

This takes us back to finance, specifically to a monetary system based on fiat currency which depends for its value on our collective trust in the people managing it.

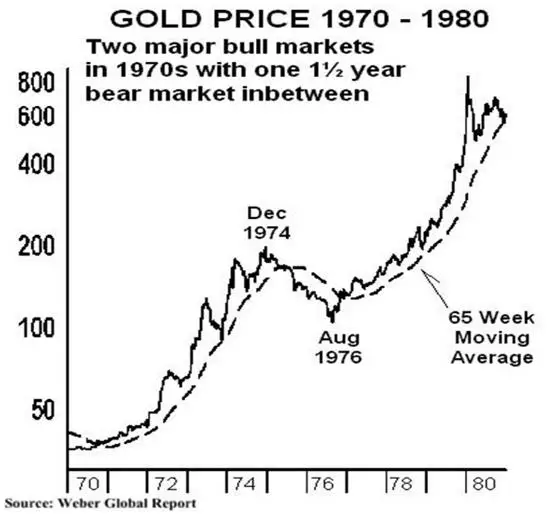

The Fed will respond to an oil crisis by cutting interest rates back to – or below – zero. But will this be met with euphoria as in the past or with skepticism, as happened in Europe recently? If it’s the latter, remember what gold did the last time there was both an oil shock and a loss of faith in government: